Can We Change the Goals of a Toy RL Agent?

1 - Introduction

Inspired by “retargeting the search” (Wentworth, 2022), we investigated a toy microcosm of the problem of retargeting the search of an advanced agent. Specifically, we investigated (1) whether or not we could locate information pertaining to “goals” in a small RL agent operating in a toy open-ended environment, and (2) whether we could intervene on the agent to cause it to pursue alternate goals. In this blog post, I detail the findings of this investigation.

Overall, we interpret our results to indicate that the agent we study possesses (at least partially) retargetable goal-conditioned reflexes, but that it does not possess any form of re-targetable, goal-oriented long-horizon reasoning.

The rest of this post proceeds as follows:

- Section 2 briefly outlines past work that has interpreted planning in RL.

- Section 3 outlines the agent (a 5M parameter transformer) and environment (Craftax, a 2D Minecraft-like environment) we study.

- Section 4 explains one approach we tried: re-targeting the agent by using probes to find representations of instrumental goals. We had little success with this approach.

- Section 5 details another approach we tried: intervening on the agent’s weights. We found that sparse fine-tuning localises small subsets of parameters that determine which rewards the agent maximises.

- Finally, Section 6 summarises our work.

2 - Related Work

The most directly relevant work is a paper by Mini et al. (2023) that investigates a maze-solving agent. They find evidence of goal misgeneralisation being a consequence of an agent internally representing a feature that is imperfectly correlated with the true environment goal, and find that intervening on that representation can alter the agent’s behaviour.

Also related is work by Taufeeque et al. (2024, 2025) and Bush et al. (2025) in which a model-free RL agent is mechanistically analysed. This agent is found to internally implement a complex form of long-horizon planning - bidirectional search - though the environment is such that re-targeting is infeasible. A summary of this can be found here.

3 - Setting

The findings in this blog post focus on a transformer-based, model-free agent. We focus on a Gated Transformer-XL (henceforth, GTrXL) agent (Parisotto et al. 2019). GTrXL agents are parameterised by a decoder-only transformer that operates on a buffer of past observations. We choose a GTrXL agent as it is SOTA in the environment we study (Gautier, 2024).

The environment we study is Craftax (Mathews et al., 2024). Craftax is a 2D Minecraft-inspired, roguelike environment in which an agent is rewarded for completing a series of increasingly complex achievements. To complete achievements, the agent must

survive, fight monsters, gather resources and craft tools.

Following Gautier (2024), we train an approximately 5 million parameter GTrXL agent for 1 billion environment steps using PPO. This agent receives a symbolic representation of the environment. However, for ease of inspection, all figures use pixel representations of the environment. An example Craftax episode is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Example of the trained GTrXL agent playing Craftax.

We chose this environment as it possesses properties we believed might encourage a long-horizon reasoning capability that could be aimed towards different goals and subgoals:

- Open-Ended: There is no single “end goal” that must be achieved. Rather, the agent earns rewards by completing a range of different tasks.

- Hierarchical Tasks: Many tasks have prerequisites (e.g. making pickaxes requires a crafting table, which requires wood) so that, if pursued, they naturally suggest instrumental goals (i.e. the prerequisite tasks).

- Common Capabilities: Different tasks involve applying a common set of capabilities (such as survival, combat and navigation) in different ways in different scenarios.

4 - Approach 1: Representation-Based Retargeting

We considered two approaches to retargeting the GTrXL agent to pursue goals of our choosing. In this section, I now detail the first approach we tried: retargeting the agent by intervening at the level of its representations.

The motivation for this approach was that, if the agent did possess some goal-based reasoning mechanism, one possible way for it to keep track of whatever active goal it is currently pursuing would be for it to internally represent that goal within its activation. If this were the case, we might plausibly be able to change the agent’s long-run behaviour by simply intervening to change this active “goal representation”.

4.1 - Method

To determine whether the agent did internally represent goals, we used linear probes. Specifically, we trained linear probes to predict the following candidates for different goals and instrumental goals we thought the agent might pursue:

- Next Completed Achievement - what is the next achievement completed by the agent for which it receives reward?

- Next Item Gathered - what is the next type of item the agent will gather?

- Next Item Crafted - what is the next item that the agent will craft?

- Next Interaction - what is the next square in the agent’s current observation that the agent will interact with?

We aimed to then use the vectors learned by these probes to intervene on the agent’s representations in a manner that we hoped would be akin to changing the agent’s goal. For instance, we thought we might be able to use the probe vectors as steering vectors for different goals.

4.2 - Results

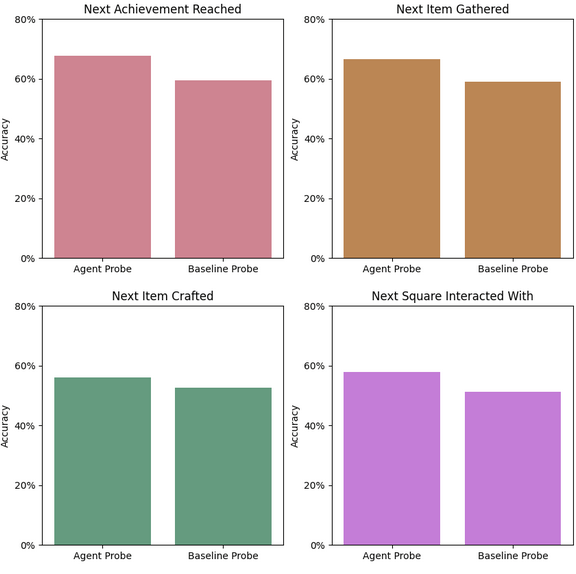

Figure 2 shows the accuracy of linear probes trained to predict these goal targets using the agent’s activations, relative to baseline linear probes that were trained using the raw observation as input.

Figure 2: Accuracy of probes trained to predict potential instrumental goals.

Figure 2 shows that, whilst these probes achieve high accuracy, so too do the baseline probes. Note that the baseline probes perform so well here as, given the agent’s observation and inventory, it is often clear what actions are best to perform next. We take this to mean that the agent does not reason by linearly representing the above goals. We also find that intervening on the agent using the vectors learned by these linear probes as steering vectors does not cause the agent to pursue other goals.

5 - Approach 2: Weight-Based Retargeting

We also investigated a weight-based approach to retargeting the agent, which we found to be more successful. The motivation for this approach comes from skill localisation in LLMs: Panigrahi et al (2023) find that you can recover much of the performance of fine-tuning LLMs by transplanting a sparse subset of weights from a fine-tuned model to a base model.

5.1 - Method

Motivated by this, we sought to investigate whether we could localise modular “goal weights” in our Craftax agent. The idea here is that, even if the agent does not represent goals within its activations, it may embed goal-centric evaluation within its weights. That is, there may be a set of weights that evaluates the favorability of different actions with respect to different goals. If we can find such “goal weights” – which we loosely understand to be a set of weights that implement an evaluation circuit that evaluates actions with respect to different goals – we could then potentially intervene on these weights to get the agent to pursue alternate goals.

More precisely, we perform the following steps:

- Fine-tuning with Different Rewards. First, we fine-tune the trained agent for 50m transitions on additional Craftax episodes with a modified reward structure. For instance, in these alternate episodes, the agent might only be rewarded for killing cows. We fine-tune the agent whilst heavily regularising absolute parameter diffs.

- Weight Transplanting. Then, we transplant a small subset of weights from the fine-tuned agent to the base agent. We do this by grafting only the top-K percentage of weights based on the magnitude of how much they change during fine-tuning.

- Measuring Behavioural Change. Finally, we measure the reward the base agent achieves under the alternate fine-tuning reward structures when only the top-K percentage of weights are grafted on to the base agent.

The different reward structures we fine-tune the agent on are as follows:

- Hunt Cows/Snails/Zombies/Skeletons. The agent is rewarded only when killing cows/snails/zombies/skeletons. There are no hard prerequisites for these tasks, though they are made easier by crafting weapons.

- Make Torches/Arrows. The agent is rewarded only for making torches/arrows. To make a torch/arrow, the agent must bring wood and coal/stone to a crafting table.

- Gather Coal/Iron/Stone/Wood. The agent is rewarded only for mining coal/iron/stone/wood. Gathering coal and iron requires a stone pickaxe, gathering stone requires a wood pickaxe, while gathering wood has no prerequisites.

- Place Stone On Water/Lava. The agent is rewarded only when placing stone blocks on water/lava. This requires gathering stone, and navigating to water/lava.

Other than the final two reward structures, these reward structures all correspond to tasks that are instrumentally useful in Craftax, and that the agent is rewarded for the first time they complete them in normal Craftax episodes. Further, the final two reward structures correspond to actions that are instrumentally useful to the agent for navigation/exploration. As such, we believed these reward structures could be plausible goals the agent possessed.

5.2 - Results

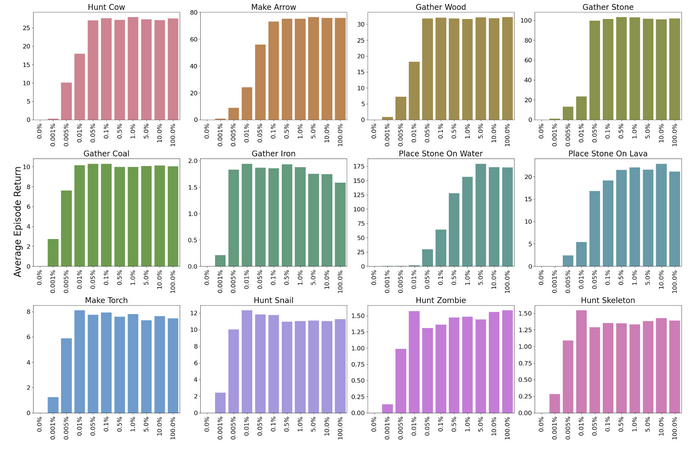

The rewards achieved by the base agent, when different amounts of fine-tuned parameters are grafted onto it, are shown in Figure 3. Here, the average episode return is the return achieved by the agent under each different reward structure over 1000 episodes (e.g. the “hunt cow” results show the return achieved by the agent when the environment only rewards agents for killing cows). Transplanting 0% of weights corresponds to the base agent without fine-tuning. Transplanting 100% of weights corresponds to the fine-tuned agent.

Figure 3 \- Average return achieved by the agent across 1000 episodes with different reward structures when grafting on different percentages of weights (in order of most-changed during fine-tuning) from fine-tuned agents to the base agent. Returns are normalized so that 0 is the average return achieved by the base agent for each reward structure.

Figure 3 shows that transplanting over a very small subset of weights – e.g. between 500 to 50,000 out of 5,000,000 – from agents fine-tuned on alternate objectives to the base agent causes the base agent to perform as well as the fine-tuned agent on these alternate objectives. Examples of episodes in which we transplant fine-tuned 50,000 parameters to the base agent are shown below.

Figure 4: Example of an episode after transplanting the top 1% weights from the fine-tuned torch-crafting agent.

Figure 5: Example of an episode after transplanting the top 1% of weights from the agent fine-tuned to build bridges across water.

Figure 6: Example of an episode after transplanting over the top 1% of weights from the agent fine-tuned to kill cows.

Furthermore, a few interesting observations can be made about the specific sets of weights that change during fine-tuning, and that we graft over.

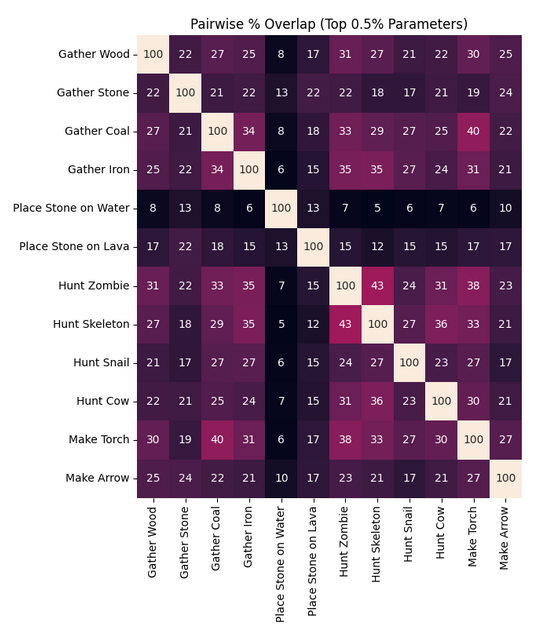

- Inter-Goal Overlap. There is notable inter-goal overlap between the top-k% of weights. Figure 7 shows the overlap between the top-0.5% most-changed weights for pairs of rewards (overlaps for other values of top-k are in Appendix A). Interestingly, the patterns of overlap make intuitive sense. For instance, the weights corresponding to hunting zombies and hunting skeletons overlap significantly, which makes sense as both goals require similar capabilities (e.g. exploration, survival, combat).

Figure 7: Overlap (%) between the top-0.5% (25,000) of most-changed weights for different fine-tuning reward structures. An overlap of 50% corresponds to 50% of the top-0.5% of parameters being shared.

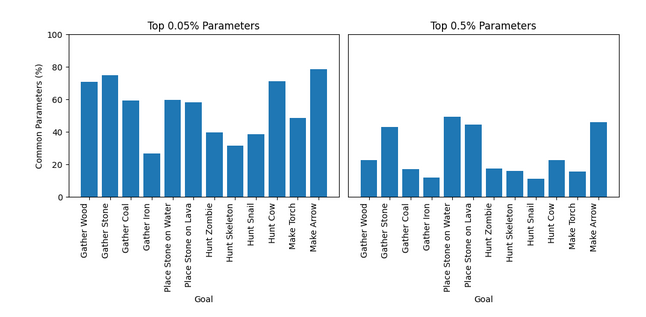

- Intra-Goal Overlap. There is significant overlap between the top-k% of weights when fine-tuning on the same rewards with different environment seeds. Figure 8 shows the inter-goal overlap for the top-0.05% and top-0.5% of weights that are common when fine-tuning on each reward structure with 5 independent seeds. Overlaps for alternate values of top-k are in Appendix B. For context, if sampling randomly, the expected number of common weights is ~zero. We take the overlap between the weights as evidence that (subsets of) the weights changed by our fine-tuning procedure do truly correspond to tasks / goals associated with each reward structure.

Figure 8: Overlap (%) between the top-0.05% (2,500) and top-0.5% (25,000) of most-changed weights when fine-tuning the agent on the same reward structures with 5 independent environment seeds. An overlap of 50% corresponds to 50% of the top-k% of parameters being shared across all 5 fine-tuned checkpoints.

- Inter-Goal Modularity. We find that, for the most part, the top-k weights for each reward structure are modular. That is, when grafting over the top-k weights for two separate reward structures simultaneously (and taking the mean weight for any weights that are common), the agent will pursue both associated goals. This is illustrated in Figure 9, in which we show the portion of the increase in return when grafting on the “main goal” (relative to return achieved by the base agent with no fine-tuning) that is retained when grafting on the weights for both the “main goal” and an “additional goal”.

Figure 9: The portion of the increase in return when grafting on a “main goal” (relative to the base agent without any fine-tuning) that is retained when grafting on the weights for both the “main goal” and an “additional goal” when grafting on the top-0.05% (2,500) and top-0.5% (25,000) of most-changed weights. Note that the diagonals correspond to only grafting weights for the “main goal” and so are all 1 (meaning the return obtained is unchanged).

6 - Discussion

So - were we able to retarget an RL agent by locating and intervening upon goal-relevant information?

As shown by the fact that our linear probes do not outperform the baseline, the agent’s internal representations contain no additional information about goals relative to the agent’s observation. Thus, the agent does not appear to internally represent explicit goals. As such, we are unable to effectively control the agent by intervening on these goals (at least, with our technique).

However, does this mean this agent does not possess goal-relevant information that can be intervened upon to control the agent? Our results in Section 5 are inconclusive regarding this.

On the one hand, it does seem as though there are small subsets of the agent’s weights that are associated with specific goals, and that can be intervened upon to steer the agent towards the pursuit of different goals. Plausibly, these weights are goal evaluation weights that evaluate the attractiveness of different actions with respect to different goals, and by intervening on these weights we are increasing / decreasing the evaluative strength of the weights associated with different goals.

However, on the other hand, this is likely not an evaluation based on long-term planning. Instead, it seems to be an immediate association, like a shard activating when certain conditions apply. From this perspective, our goal fine-tuning would be modifying the relative strength of shards. For instance, perhaps all the “Gather Coal” fine-tuning does is to strengthen the activation of heuristics that are relevant to gathering coal.

Further, it seems that, rather than having a common set of “goal weights” that could be re-targeted towards any arbitrary end, the agent possesses sets of weights that are tied to specific goals. Thus, whilst we can seemingly intervene to cause the agent to pursue specific goals it acquires during training, it is unclear how we could use our methodology to intervene on the agent to encourage the pursuit of arbitrary goals. This might not be a problem for retargeting more advanced, LLM-based agents as, having been pretrained on vast quantities of text, such agents may have learned goals about anything we might want to retarget them towards.

Appendix

A - Inter-Goal Weight Overlap for Different Top-K%

Figure 10: Overlap (%) between the top-k% of most-changed weights (for different values of k) for different fine-tuning reward structures. A pairwise overlap of 50% corresponds to 50% of the top-k% of parameters being shared.

B - Intra-Goal Weight Overlap for Different Top-K%

Figure 11: Overlap (%) between the top-k% of most-changed weights when fine-tuning the agent on the same reward structures with 5 independent environment seeds. An overlap of 50% corresponds to 50% of the top-k% of parameters being shared across all 5 fine-tuned checkpoints.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: